William Owen enlisted at the Cape Mounted Rifles recruiting office in London, England. He joined on the 3rd of December 1899 and was soon on a ship bound for South Africa where he joined his unit to fight in the Anglo-Boer war. He served in the Transvaal, Orange Free State and finished the war in the Cape Colony where the C.M.R. spent frustrating but sometimes exciting months chasing groups of Cape Rebels through the bush.

William Owen enlisted at the Cape Mounted Rifles recruiting office in London, England. He joined on the 3rd of December 1899 and was soon on a ship bound for South Africa where he joined his unit to fight in the Anglo-Boer war. He served in the Transvaal, Orange Free State and finished the war in the Cape Colony where the C.M.R. spent frustrating but sometimes exciting months chasing groups of Cape Rebels through the bush.

In 1902 Owen was one of 18 men sent to London as part of the Coronation contingent, before returning to South Africa to continue his service in the C.M.R.

The C.M.R. had established their headquarters at Umtata with bases in the outlaying districts. The C.M.R. could best be likened to a frontier police unit, although trained as soldiers their duties ranged from recording births to hunting murderers and it required a special kind of man to carry out the task. The men patrolled the bush, dealing with brandy smugglers, witchcraft, health inspectors and jailors. They formed the function of Commissioners of Oaths and customs officers.

A few extracts from "Boot and Saddle" by P.J. Young can give an idea of the life Owen led from 1902 to the outbreak of the first world war.

"The life in the barrack-room was dull and somewhat petty. To live, work, eat, drink and sleep together on terms of equality presented a unique opportunity to understand each other. Some played games, some talked football, others got into endless arguments on various topics. The latter sometimes caused friction, finally ending up by one man inviting another to "step outside". The recruits arrived in small batches at Umtata and had to adapt themselves to the conditions that they found to be already in existence. The standard of discipline was high. A particle of impertinence offered to the most Junior N.C.O. was a crime and was punishable as such.

The average C.M.R. was a man with a good deal of simplicity. His code of living was simple; he saw life as a series of incidents with which he had to deal in a practical way. His pleasures were few: tennis, football, a gymkhana now and again, and an occasional "smoker". There was little opportunity to cultivate the mind, and our quarters, hopelessly bare and crude, offered no inducement to the exercise of individual taste. Few books came our way; we read anything. Our religion was relegated to the dim background of our mind. Socially we saw too much of each other on the outposts, and were hard put to find some diversion. Nevertheless, on the whole there was a good deal of lightheartedness."

In 1906 Owen was part of a small group of 6 Maxim machine guns (1 officer and 20 men) who were sent to Natal to help suppress the Zulu Rebellion, often called the Bambata Rebellion after the rebel leader. Chief Bambata ruled the Amazondi tribe in the area near the Tugela river.

The C.M.R. detachment was engaged in a number of skirmishes with some hopelessly outgunned rebels and the detachment returned to the Cape without loss.

In 1911 Owen was promoted to Sergeant and in 1913 the various Mounted Rifles units were merged into a Brigade with 5 units. The Cape Mounted Riflemen became the 1st South African Mounted Riflemen. In that year the S.A.M.R. was called to Johannesburg, where they participated in crushing the riots of the striking gold mines. In this action, 22 miners were killed and 200 wounded. While they were in Johannesburg Owen was promoted to Lieutenant.

Lt. Owen's participation in the First World War is described in the Battle of Sandfontein. Owen survived and was sent back to the South African positions that same day due to the severity of his wounds. He had to have particles of shot removed from his face and was blinded for life. He was released from service as an honorary Captain and after his release his private life took a series of depressing and dramatic turns, largely due to his own making.

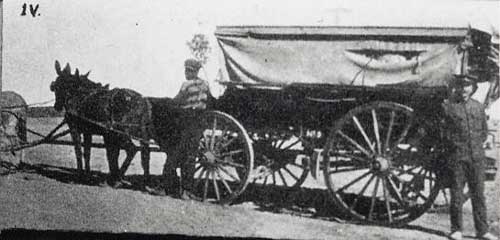

The ambulance with which the Germans sent the blinded Lt. Owen back to the Union lines:

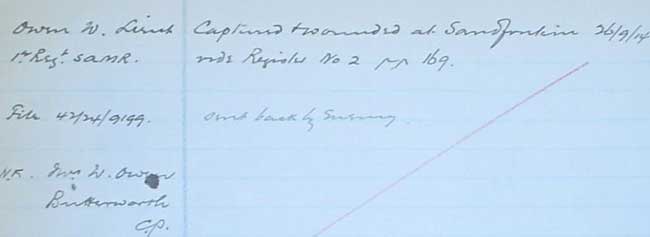

The register entry for Wounded and POWs notes that Lt. owen was "Sent back by enemy":

William Owen was awarded the following medals:

P.J. Young writes:

"As far as the general public is concerned, the incidents of the Sandfontein tragedy have never been made known.....

There was a little cemetery lying a short way beyond the hill. Our dead and the German dead were buried there. Somewhere, somebody still remembers them..."